Lu Yu (733-804 or 715-803)

Lu Yu lived during China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907) and authored the groundbreaking “The Classic of Tea” (Cha Jing or Ch’a Ching), considered the starting point for tea history due to the scarce and fragmented information on tea before Lu Yu’s time. He became an esteemed historical figure, sometimes elevated to deity status. As a tea master and writer of the first book on tea, Lu Yu laid the foundation for Chinese tea culture.

Lu Yu lived during China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907) and authored the groundbreaking “The Classic of Tea” (Cha Jing or Ch’a Ching), considered the starting point for tea history due to the scarce and fragmented information on tea before Lu Yu’s time. He became an esteemed historical figure, sometimes elevated to deity status. As a tea master and writer of the first book on tea, Lu Yu laid the foundation for Chinese tea culture.

Various accounts of Lu Yu’s life tell of his orphanage upbringing by a Buddhist monk. Rebelling against monastic life, he joined a theater troupe, becoming a popular clown and playwright. Despite his success, he yearned for education, which an influential fan enabled, allowing Lu Yu to become a scholar. He spent five years in seclusion writing “The Classic of Tea,” a comprehensive book on tea covering the plant, cultivation, picking, tools, water quality, and techniques. More than a manual, Lu Yu’s book was a scholarly work reflecting deep familiarity with all aspects of tea culture, instantly propelling him to fame.

Monk Eisai (1141 – 1215)

Monk Eisai was pivotal in Japanese tea history, introducing matcha to Japan in 1191, tightly linking tea with Zen Buddhism. He established the tea-drinking method during the Southern Song Dynasty and is revered as the founder of Japanese tea culture. Eisai brought tea seeds from China, sowing them on Mount Sefuri in Fukuoka and instructing the monk Myoe to cultivate them in Kyoto, initiating Japanese tea cultivation. His book “Kissa Yojoki” (1211) explained tea’s health benefits for vital organs and as a medicinal aid, detailing plant parts and dosages for ailments.

Sen No Rikyu (1522-1591)

Sen No Rikyu developed the quintessential Japanese tea ceremony performed to this day. Born in Sakai during Japan’s warring period, Rikyu performed tea ceremonies for feudal lords Nobunaga Oda and Hideyoshi Toyotomi. As a merchant’s son and apprentice to Takeoo Joo, Rikyu refined his master’s trend into a spiritual and artistic ceremony. He set the chado rules, embracing austerity, humility, simplicity, and imperfection. His innovations in tea ceremony aesthetics and the tea house design significantly influenced Japanese culture. Tragically, he was ordered to commit seppuku by Emperor Hideyoshi under ambiguous circumstances, a demise he faced with dignity after a symbolic final tea ceremony.

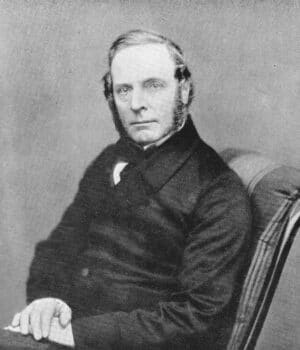

Robert Fortune (1812-1880)

Robert Fortune, a Scottish botanist, was sent by the British East India Company to China in 1848 to uncover tea production secrets. The British faced supply issues with tea imports due to Japan’s closed market, spoilage during long sea voyages, and China’s monopolistic pricing. Fortune’s clandestine journey involved disguising himself as a Chinese merchant, exploring tea regions, and documenting the black tea production process. Escaping a bounty on his head, he brought tea seeds, tools, skilled Chinese workers, and plants to India, kickstarting Indian tea production in the Himalayan foothills of Assam and Darjeeling.

These historical figures are just a few who contributed richly to the history of tea, demonstrating the significant impact one person can have. Perhaps it’s something to ponder over your next cup of tea?